The core focus of MERGe Lab is building better robots through intentional design of their bodies. As robots are deployed outside of the lab and the factory, their bodies will need to match the wide variety of human environments. Our current suite of robot materials, structures, actuators and sensors are not adequate for human contact, let alone the wide range of environments that humans live in.

Current robots can do impressive grasping tasks with cameras and other forms of computer vision. However, humans are able to accomplish more dexterous manipulations without any vision, such as striking a match, juggling or solving a Rubik’s cube. There is a clear need to build the tactile sensors, end effectors and algorithms to imitate non-visual human manipulation.

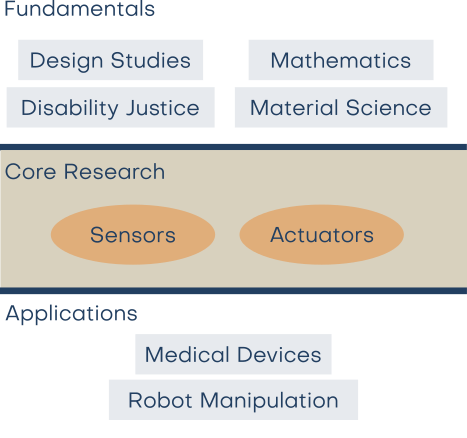

In this project, the goal is to have a robot be able to reach inside a box, fumble around, and eventually find an object inside without the use of cameras. This is a contact-rich task that will require identifying the box walls, searching for an unknown object and executing the optimal grasp to take it out of the box. With our past work in fluidic innervation and object sensing, we are confident not only in our ability to achieve this task, but also potentially solve grasping a specific object in clutter.

Since the sensorization technique of fluidic innervation is based off of 3D printing, we have significantly more design control over sensor placement, geometry and the structure which the sensors are embedded within. This offers enormous potential to bridge the simulation-to-reality (sim2real) gap, enabling us to build off of our prior work on optimized sensor placement for soft robotics.

In this project, we will build off of simple lattices, as their repeated geometry allows for simpler mathematical models and easier characterization. We will then build up to more complex lattice structures, such as handed shearing auxetics before moving to more stochastic structures like Voronoi foams.

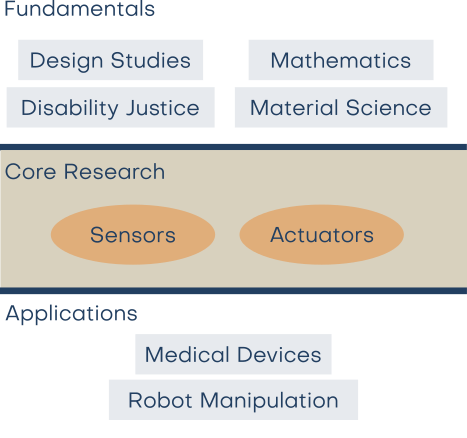

Beyond our core research focus of building robotic sensors and actuators, we are also interested in:

Some potential projects in these directions include::

Our systems have outperformed similar soft robots in power efficiency (20x more efficient) and speed (2x faster), outperformed similar modular robots in locomotion (10x faster) while maintaining a high strength-weight ratio (76x), and created the largest sensorized soft robotic dataset (18 hours).

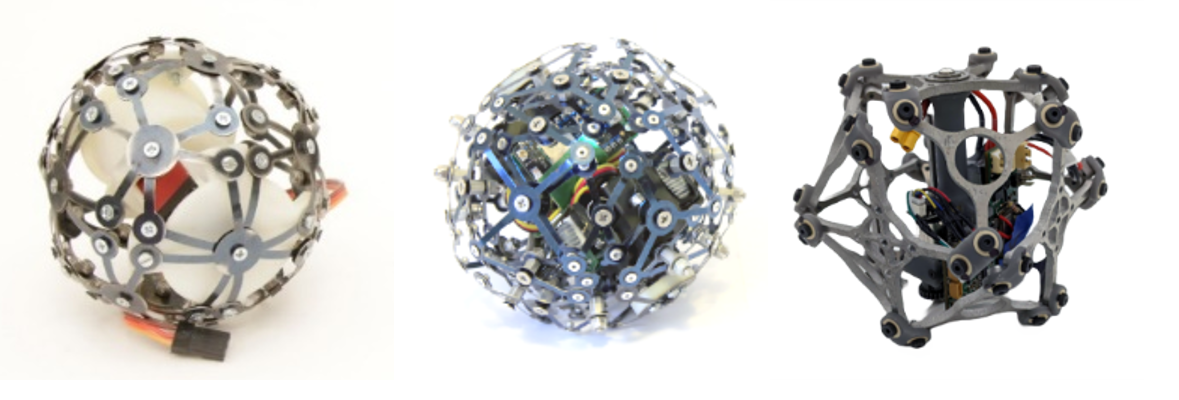

Auxetics are materials with a negative Poisson’s ratio. Unlike, say, a rubber band, which gets skinnier as you stretch it, auxetic materials get thicker as you stretch them due to their internal geometry. In this project, we applied actuation directly to a spherical auxetic shell to create modular robots with motor-driven volume expansion (Auxbots). By controlling the shell’s geometry, we could create robots optimized for speed and expansion ratio (390% volume expansion in 0.2 seconds) or for force output (135 N max, or 76x strength-weight ratio, one of the highest ratios of any modular robot). We could explicitly make trade-offs between stiffness, speed, and force as a direct consequence of how the geometric parameters affect the overall system behavior.

We then connected multiple auxbots together for more complex actuation, similar to how biological cells come together to form tissues and organs. With the speed and size optimized auxbots, we created a 2x2x2 cube that could move forward, turn, and flip, due to the high impulse response. Meanwhile, with the force optimized auxbots, we created a flipper-like locomotion by tying adjacent auxbots together with a wire. This simultaneous lifting and bending action led to a seven-bot quadruped that could carry loads up to 1.5x its total weight (2 kg), even with some auxbots stalling out. Auxbots thus demonstrate not only how geometry gives greater control of robot performance but also offers a potential pathway to address the gap between simulation and reality.

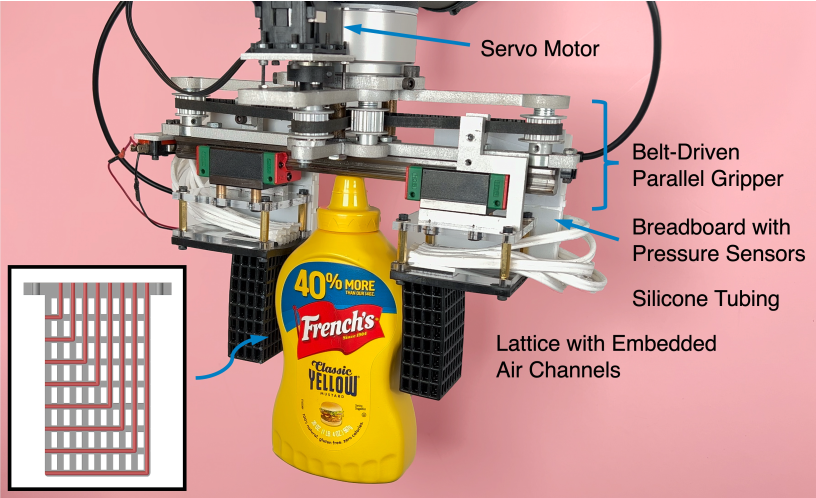

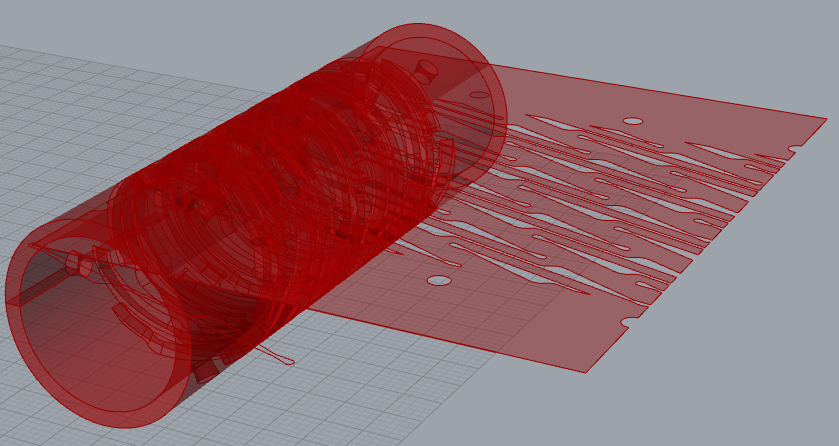

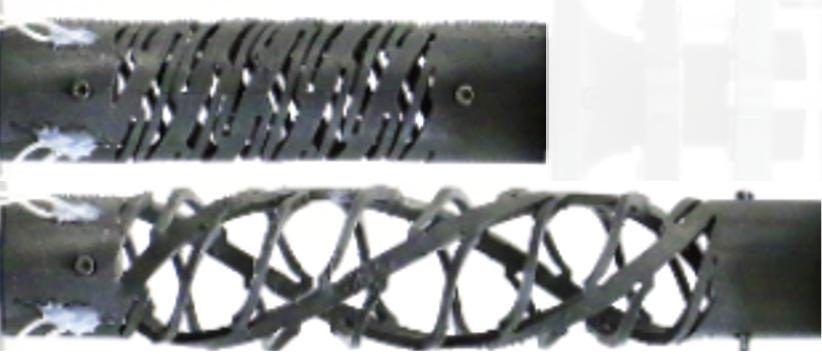

Normal auxetics expand until they reach a symmetric point. After that point, further expansion leads to a collapse down to their mirror image. By contrast, we discovered a materials called handed shearing auxetics (HSAs) that have a chirality. Thus, if a left-handed and a right-handed HSA are rotated against one another, they will fight against the other’s rotation and “lock-in” their position.

This approach enabled us to create several soft robots just by changing the geometric structure. We created a 4 degree-of-freedom robotic platform directly from HSAs by placing opposite handed HSAs in a 2x2 grid and attaching a motor to each HSA. Similar high degree-of-freedom platforms would require significantly more infrastructure, like the six prismatic joints needed for a Stewart platform. Likewise, we created robotic fingers from the HSAs by drawing a line through the pattern. This line would act as a strain-limiting layer, forcing the entire structure to bend inwards. Since the HSA gripper is motor-driven, it is 2x faster at opening and closing, 20x more power efficient, and occupies a smaller footprint than standard soft pneumatic-based grippers, all while maintaining a similar grasping performance.